11/3/06

Hello Olga,

I have just spent a couple of days on your site and am very sorry

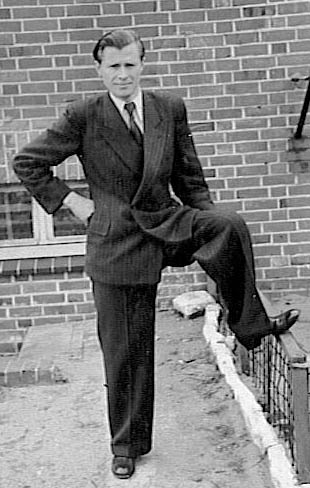

that I did not do so while my father was still alive. His name

was Gregory Bogdan (Bogdanov). He died in June of this year. I

have photos and some information about his life but am wondering

if it is possible to find out more. I know he was in Fischbeck

from approximately 1946 to 1951 when he left for America. I know

he either left or was removed from Ukraine, in the area between

Sumy and Romny some time in 1942 or 1943. He was born in Ukraine.

I wonder if it is possible to find out where he was in Germany

during the war. I assume it was in one of the labor camps around

Hamburg but have no basis for this assumption except that he was

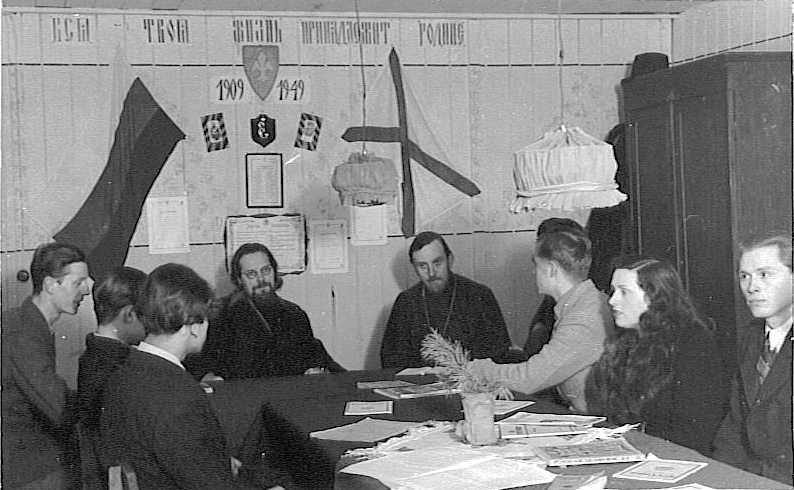

in Fischbeck. I have some photos given to him by friends during

that time and a newssheet dated Jan 4 1948 (in Russian) regarding

elections for camp commandant. The address is Hamburg-Noegraben,

Fischbeck, DP Camp No. 514. If there is anyone who knows of people

(probably Orthodox religion as this appeared to be prevalent there)

who were there I would like for them to contact me. Thank you,

Nina Bogdan anin99@comcast.net

Nina Bogdan submitted these photos

4/19/2010 Hi Olga,

I

have viewed your website, wonderful. I live in Australia. I'm trying

to track information on this man.

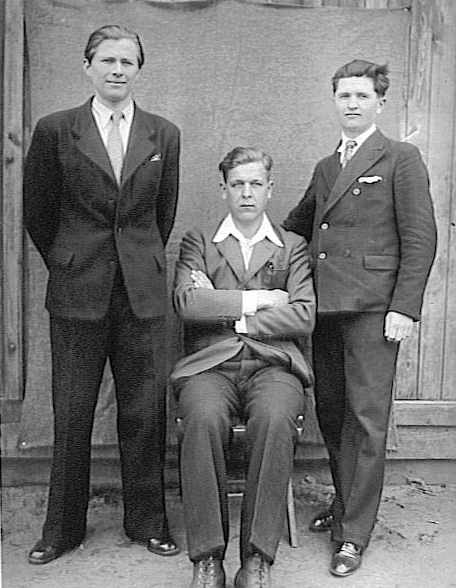

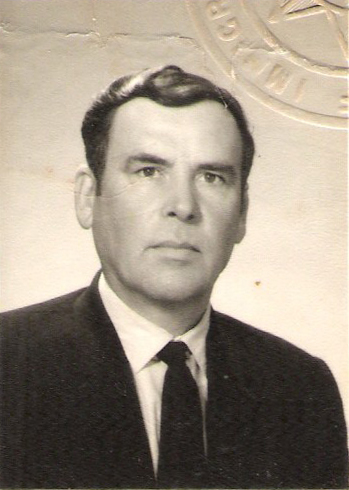

He was in DP Camp 514 Fischbek WW2 – Born in Dubno Poland

[now Ukraine].

My mother passed away and I found this photo, which I believe

to be my father.

My mother was also in DP Camp 514 Fischbek WW2. Her name was Ekaterina

Andriivna, formerly: Havrysh, married name: Palaniza (Palianycia,

Palianytsia)- different spellings – Born Dubno Ukraine.

I would like any photos or more information on my mother also.

I have aunties, uncles & sisters who I don’t know and would like

to contact.

We have searched the internet and have not came up with anything much at

all.

If anyone knows this photo or can help with more information would be greatly

appreciated. meanstreetaustralia@hotmail.com Thank

you

I

have viewed your website, wonderful. I live in Australia. I'm trying

to track information on this man.

He was in DP Camp 514 Fischbek WW2 – Born in Dubno Poland

[now Ukraine].

My mother passed away and I found this photo, which I believe

to be my father.

My mother was also in DP Camp 514 Fischbek WW2. Her name was Ekaterina

Andriivna, formerly: Havrysh, married name: Palaniza (Palianycia,

Palianytsia)- different spellings – Born Dubno Ukraine.

I would like any photos or more information on my mother also.

I have aunties, uncles & sisters who I don’t know and would like

to contact.

We have searched the internet and have not came up with anything much at

all.

If anyone knows this photo or can help with more information would be greatly

appreciated. meanstreetaustralia@hotmail.com Thank

you

1/26/2010 Hi Olga:

Here are some things that I remember from the Fischbek

DP Camp, near Hamburg, Germany. Please post this on your website, if

you think it’s useful.

1. Fischbek is the German spelling. Fischbeck is

in English. This may lead to confusion, if people are doing

a search on the Internet.

2. My parents and I lived at 2 Rostweg,

Fischbek from 1951 to 1957.

The population at that time consisted mostly of Eastern Europeans – Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Latvians. Some German families also lived in this camp.

The camp was shrinking at that time. People were leaving the camp by emigration to other countries. Others moved to new housing, as Germany was rebuilt.

More than half of the original barracks had been demolished on the east and south sides of the camp. Around 1957, on the south side of the camp, new housing was going up for German Army Officers.

3.The camp had a Russian Orthodox church. I remember attending church services on holidays, especially Easter. I also remember attending funeral services. Therefore, there must have been a cemetery nearby. Anyone looking for family, perhaps can contact the Russian Orthodox Church in Germany.4.The

train station was in Neugraben. It

took about an hour to walk there. We used to take the train

to Harburg, and then to Hamburg. We

emigrated to the USA in 1959.

5. There

was a second DP camp nearby. I

think the name was Falkenberg. It was within

walking distance; we visited with people the occasionally.

6. I

was in Germany in October 2000, and took a drive to Fischbek. Rostweg,

the street, is still there. But the whole camp is gone. The

place is now a residential area.

If anyone is

interested in more information, they can contact me - at toly48comp@verizon.net

Best Regards – Anatoly Kurjaninow

On

3/26/11 Hi

Olga,

I would like

to know what it is going to cost for a search for information on my

parents who were at camp 514 Fischbeck Hamburg Noegraben. On your site

there is a photo of members of the camp and I think one of the women

in that photo is my mother. anastasia abela anastasia2654@hotmail.com

10/4/09 Hi Olga:

My name is Anatoly Kurjaninow. I

live in New Jersey. I came across your site as I was searching for

info on the Fichbeck camp, near Hamburg. I and my family lived there

in the early 1950's before we emigrated to the USA.

My email is toly48comp@verizon.net Anatoly Kurjaninow

21/1/05, From: Alan Newark braveheart180203@hotmail.com

Subject: Polish Life in West Germany After 1945 SR, April 2003

Reprinted from April 2003 Sarmatian Review: http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~sarmatia/

Polish Life in West Germany After 1945 -- A Case Study on Hamburg

Angelika Eder

The author wishes to thank Judith Fai-Podlipnik and Karl Bahm for their critical

and supportive comments on this paper.

The structure of the Polish group in Germany reflects the complex history of German-Polish relations and the impact the Cold War had on the history of both nations. As a result, Poles in Germany are a very heterogeneous group with regard to their migration history and their legal status.(1)

Poles in Hamburg and elsewhere in the Federal Republic of Germany include: former labor migrants from Prussian Poland and their descendants; former forced laborers and prisoners of the Second World War who became Displaced Persons under Western Allied occupation and were later classified as "stateless aliens" (Heimatlose Ausländer) under German administration after 1950;(2) various groups of political refugees with residence permits of different grades; Aussiedler, or ethnic Germans living outside Germany, with their families; and other migrants who all came in different waves depending on the state of German-Polish relations and the political situation in Poland.(3) After 1990 new "circular" forms of migration began, such as seasonal workers on construction sites in Berlin and in south German vineyards.(4) Return to Poland was again possible and the decision to migrate to Germany no longer entailed a permanent move.

This is the context of Polish life in Germany that is the focus of this paper. I am going to look at different groups of migrants from Poland as parts of a community, even though a unified Polish community does not exist in Hamburg. To this end, I am going to employ the notion of "Polish life" in Hamburg which will take all people of Polish background into consideration. Due to gaps in the archival records (which constitute one part of the Poles' history in Germany), there are still more questions than answers about the lives of Poles in Germany. A primary source of information I draw on in this paper is interviews with people of Polish background who live in Hamburg.(5)

Currently about 19,000 people with a Polish passport and 100,000 people with biographical bonds to Poland live in Hamburg alone, a city of 1.7 million inhabitants.(6) They are not, however, as visible on the city scene as one would expect of the third largest group (or even the largest, if one counts heritage as well as official nationality) of non-Germans in Hamburg. Here in Hamburg, the history of Poles in Germany seems to be a hidden one. If one talks about Poles in Germany, most people think of "Ruhr Poles," worker migrants who settled in the Ruhr area during the years of the German Empire and who exemplify "the success story" of assimilation of foreigners into Germany.(7) Around 500,000 people of Polish origin lived in the Ruhr area in 1914, some 100,000 in Berlin and another 150,000 in other German regions, including 15,000-21,000 in and around Hamburg.(8) In the Prussian town of Wilhelmsburg (today a part of Hamburg and at that time called Little Warsaw), 1,800 Polish households with approximately 5,000 people were registered in 1919/20.(9) In spite of these figures, local memory ignores the fact that there has been a long continuity of Polish life in that area.

The Polish state was reestablished in 1918/19, after 123 years of partition. Since the majority of Polish workers in Prussian Poland had German citizenship, they were allowed to stay there after that time. Generally speaking, foreign Polish labor migrants had been employed only as seasonal workers until 1914.(10) In this context, national identity becomes a difficult topic: the changing borders and demographic mix over the centuries make identification difficult. The shifting of population and territories as a result of National Socialist politics added another complication, especially the Germanization policy according to which "Germanizable" Poles could be registered on a Volksliste 3 which was later used by the Aussiedler to prove their German origin.(11) Consequently, the question of citizenship and nationality between Poland and Germany has always been a delicate one. A legal definition or "legal identity" does not say much about the inner relationship of a person towards culture, traditions, and a nation's history. Therefore I am applying a somewhat subjective definition when using the terms Poles, Polish life, or people of Polish background.(12) I am assuming that people who grew up in Poland or whose parents came from Poland are somehow shaped by Polish traditions, history, mentality, and culture, that they bring their own "cultural knowledge" from Poland.(13) Thus in my study I take into consideration all groups of people who came from Poland to Germany after 1918, including the Aussiedler and their families. However, this causes quantitative problems and results in estimates rather than exact statistics. Nonetheless, it is essential to include all participants to describe Polish life in Germany after 1945.

After the Second World War, Polish life was hidden from the German public who had been aware of the liberated concentration camp inmates in 1945 but perceived DP camps as something problematic. There were very few Germans involved in organizing and attending Polish events, and their efforts were not noticeable on the German scene.

Polish life in Hamburg began to thrive at about the same time that it emerged in other parts of the region and in the Ruhr area, as well as in Berlin. In Hamburg, there were Polish workers from the Prussian part of Poland and (in smaller numbers) from other parts of the country. "Foreign" Poles returned or were expelled to Poland before or after the First World War. The Prussian Poles who decided to stay in Germany after the war organized themselves as a national minority in Zwiazek Polaków w Niemczech (Union of Poles in Germany, est. 1922) and in other associations, for example in a Polish school society for Hamburg.(14) The remaining Poles in Wilhelmsburg and other parts of Hamburg continued to have Polish church services, language classes for their children, and at least once a year a festive Polish ball.(15) After 1933 the conditions for Poles deteriorated everywhere in Germany. The German attack on Poland in September 1939 put an end to any "Polish life" in Germany. In Hamburg, its leaders and some Polish citizens were arrested, the use of the Polish language in church was forbidden, and the teaching of the Polish language became impossible.(16)

During the war, more than one million Poles were deported to work in Germany.(17) In the summer of 1944, 5,800 forced laborers from Poland lived in Hamburg alone.(18) They were liberated by the Allies in 1945 along with the concentration camp inmates and former Polish soldiers and fighters of the Warsaw Uprising of August-October 1944.(19) The Western Allies (in Hamburg, the British) coordinated their temporary shelter and food and assembled them in the Displaced Persons (DP) and Ex-Prisoners of War (PWX) Camps, separated by nations, with the plan to repatriate them soon.(20) Research on Poles in Germany distinguishes between old emigration that arrived before 1918 and new emigrants who arrived after 1945.(21) However, both groups should be considered as representing the foundation for Polish life in Hamburg after the Second World War. In October 1946, 3,886 Poles were located in Hamburg. Polish citizens numbered 1,714, German citizens 921, and the remaining 1,251 had unclear citizenship.(22) At that time, 80 percent of the 1,534 men and 180 women with Polish passports lived in a DP or PWX camp. More DPs were in camps at the borders of Hamburg, for example in the former army barracks in Wentorf which had already become a camp for Poles in June 1945.(23)

For Polish DPs the repatriation strategy of the Western Allies failed completely: in September 1945, when 80 percent of all DPs had already been repatriated to their home countries, the Poles were the largest DP group remaining in West Germany.(24) The reasons were manifold: the shift of their country's borders to the west and the resulting loss of homesteads in the east, problems with transportation capacities to the east in 1945, resistance against or uncertainty about the new political situation at home.(25) Very few of the old emigrants made use of the repatriation transports and returned to a country they had left long before the war. Later on some of them returned to Hamburg again as disappointed Aussiedler and became active in German expellee organizations.(26)

Until 1950/51 the life of the DPs and former PWXs (who had been demobilized in 1947) was supervised by British and international organizations. In 1947 the Western occupying powers began to resettle the remaining DPs in North America, Australia, and other countries after repatriation had failed. Polish DPs were still the largest national group in the camps. There were Polish church services, DP schools and vocational training courses, as well as some cultural events. The whole structure of DP life in the camps was separated from the life outside, therefore also from the life of the old Polonia. New organizations like the Stowarzyszenie Polskich Kombatantów (Association of Polish Combatants, est. 1946) had nothing to do with former Polish associations.(27) At the same time, outside the camps some old emigrants began to revive Polish life in Hamburg. They maintained old traditions by reestablishing a Catholic church service in Polish as early as June 1945 and by re-founding a local group of Zwiazek Polaków w Niemczech - Rodlo which became official in 1948.(28) For some of the old residents the chance of "bringing a piece of the home country to Hamburg" was a motive to organize language classes and a dance group.(29) For others, newly established Polish organizations and the new emigrants were of no interest at all; they remained in their German Catholic or Social Democratic milieu.(30)

For the majority on both sides, life was still separate, not the least because of their different legal status as Germans or DPs. Many DPs had not yet started to think about a life in Germany but were waiting for other options. The former DPs remember the interest of people already living in Germany whose bonds to their Polish background were renewed and encouraged by listening to the Polish language in the streets, by meeting "new" Poles and taking part in Polish life.(31) Shortly after the end of the war, Polish DPs were approached by old emigrants who welcomed the ones coming from "home."

For some of the permanent residents the presence of Polish DPs offered comfort when Germans ignored and forgot about their Polishness. The mutual understanding between some of them was like an "osmosis," one former DP remembered.(32) Some former Polish soldiers who had good connections to the British remember that they [the Poles] could help members of the old Polonia who were seen as Germans by the British, for example, with university applications or with legal advice.(33) There took place events like the traditional Polish celebration of Corpus Christi in a DP camp which attracted Polish residents from outside. On the other hand, the old Polonia invited some DPs to parties they had begun to arrange.

After DPs had been classified as Heimatlose Ausländer under German administration in 1950/51, their numbers decreased further due to migration. The reasons why some Poles stayed in Hamburg were manifold: the former DPs/PWXs I interviewed remained in Hamburg due to an ill family member or because they had many children and could not easily move; or because of a lack of options for emigration; or because they wanted to remain in close proximity to the home country, Poland.(34) Camp life continued in the six camps Hamburg had taken over from the British in 1950, but spheres of life like school and church were moved out of the camps, while the number of Polish DPs decreased. DP children went to German schools, DP families attended Polish Catholic services in Protestant Hamburg. As DP camps began to fill up with Germans, Polish life outside the camp became more important for the Poles. By the late 1950s, virtually all Polish DP families found accommodations outside the camps. At that time the first Aussiedler from Poland had already arrived. The accommodations the DPs were offered were scattered all over Hamburg. At that time, Polish organizations and especially the weekly church service also gained significance for youngsters, or for the DP children who had gone to school together.(35)

Polish life was hidden from the German public who had been aware of the liberated concentration camp inmates in 1945 but who perceived DP camps as something problematic. There were very few Germans involved in organizing and attending Polish events, and their efforts were not noticeable on the German scene. The majority of Polish DPs worked with the Allied authorities in the 1950s and did not have much contact with German colleagues. And the political events in the People's Republic of Poland, in combination with the atmosphere of the Cold War, made communist Poland the only Polish topic in the German public sphere, despite the expellees' discussions of former German territories like Silesia. Furthermore, in the 1950s the German view of Polish life in Hamburg was influenced by the political division in the migrants' organizations: Germans were suspicious of the "communist" wing and ignored the other groups.(36)

In postmodern world, "legal identity" does not say much about the inner relationship of a person towards culture, traditions, and a nation's history.

The political division between the Polish Government-in-Exile located in London and the Soviet-imposed Polish government in Warsaw affected Polish life in Hamburg just as it did elsewhere. There were liaison officers operating in DP camps from both sides, and until 1950 Warsaw was represented by a military mission (consulate) in Hamburg.(37) On the other hand, former Polish soldiers were instructed by the Polish Government in London to support the reestablishment of the old Polonia structures in 1945--and they did so until the Warsaw representatives arrived in 1948. Thus both sides were fighting for the Poles abroad. After Warsaw had established itself, London began to lose power. However, the Cold War considerably diminished Warsaw's influence.(38) In the 1950s "the big shots" supported by London "had already left," as a former DP remembered.(39)

The question remains to what extent this political split was important for Polish life in Hamburg. It is undeniable that many of the newly founded organizations, whether they included "new" or "old" emigrants, declared adherence either to London or to Warsaw. Thus Polish DP students were either members of Bratniak londynski or Bratniak warszawski, and the former Zwiazek Polaków w Niemczech was continued as Rodlo and, after a split in 1952, also as Zgoda which was supported by the People's Republic of Poland.(40) This continued all through the years: Zgoda was supported by the Polish state, Rodlo represented the firm anti-communist wing. Both claimed the Zwiazek Polaków w Niemczech's tradition for their organization.(41) In reconstructing the organizational re-establishment after 1945 it is difficult to distinguish between combined efforts of old and new emigrants until the organizational split in 1952, because all involved claimed to have revived Zwiazek Polaków w Niemczech. In later years, one can find members of different migration groups and generations in both organizations: the old Polonia, DPs, DP children and later the Aussiedler as well.

Polonia in Hamburg and elsewhere was divided between those with closer relations to the People's Republic of Poland and those who remained political emigrants, and this situation might have been one reason for the inconspicuous performance of Poles in the German public arena.

In some ways, this political split in the Polish life in Hamburg and elsewhere in Germany was of fundamental importance for Poles and for their German surroundings. But there were not so many differences between the two Polish groups concerning their daily life. During their meetings, both organizations offered an opportunity to speak Polish, to meet other Poles, to exchange Polish books, and cultivate Polish folk dances. Those who were in strong opposition to the People's Republic founded additional organizations like Stowarzyszenie Polskich Inwalidów Wojennych (Association of Polish War Invalids, est. 1948) and Zjednoczenie Polskich Uchodzców w Niemczech (Union of Polish Refugees in Germany).(42) The former DPs belonged here, especially soldiers of the Polish underground who had fought in the Resistance. They were strictly anti-communist and voted against repatriation for political reasons. They maintained close contacts with the Polish government in London. Their declining status corresponded with London's dwindling position from 1945 on.(43) The position of the former forced laborers, however, especially those not interested in politics at all, is far less clear. Some of them might have expected a more affluent life in Germany or elsewhere in the West. (44) As to the "old" emigrants who had already been active in the 1920s and became active again after the war, the situation is not clear either.(45)

I estimate that the political separation is important but it has been overestimated so far as the assessment of the structure of Polish life in Germany after 1945 is concerned. Which group one had chosen to belong to would obviously determine the fundamental thrust of their gatherings; however, I doubt that weekly or monthly events were dominated by political issues. Some of my first interviewees have been very active in rebuilding structures of Polish life in Hamburg. For them the political division was of course of great importance, but that does not mean that it had the same meaning for all members of the Polish community in Hamburg: this may be quite different in other Polish communities abroad such as those in North America. Despite the Cold War, one's former country was not far away in geographical terms, which is why some decisions might have been more pragmatic and less ideological. Hence the "old" emigrants did not always join Rodlo while many former Armia Krajowa fighters chose not to associate with one of the Zwiazek-organizations at all.(46) More interesting and less explored thus far are the relations between resident Poles and DPs. The fact, however, that the Polonia in Hamburg and elsewhere was divided between those with closer relations to the People's Republic of Poland and those who remained political emigrants might be one reason for the inconspicuous performance of Poles in the German public arena.(47)

Two other factors point to the significance of political division in the early postwar years. One was the substantial American support for noncommunists in the 1950s and ‘60s that influenced the conditions of this group of Poles. In the late 1950s, as the first Aussiedler were coming to Hamburg, support of Polish events was included in the massive support of non-German refugees from the communist Eastern Europe, the support distributed through the Free Europe Citizens Service of the Free Europe Committee. Between 1958 and 1965, American money funded a Common House which sponsored concerts, exhibits, lectures and poetry readings, language classes (Polish for beginners, English for emigrants, German for foreigners), Polish dance group practice, and meetings of Zwiazek Polaków w Niemczech-Rodlo.(48) Hamburg's government monies helped fund these events as well. Only in 1968 was an institution called Klub Polski (a meeting place mainly for former DPs) established through private means. For years, this initiative struggled to find a space without any support or interest from the German side.(49)

The second factor was religion. The majority of Polish émigrés are Catholics and religion plays a major role in their life. Therefore the organization of pastoral care and church life was always important for the Polonia. It is not a coincidence that the book best documenting Polish life in Hamburg 100 years of Polish pastoral care in Hamburg was written by a Catholic priest.(50) Not surprisingly, priests and participants in Polish Catholic life were anti-communist. The next group of migrants from Poland, the Aussiedler and their family members, is by far the largest and the most difficult to assess because of their heterogeneity.

In the late 1940s, the flow of millions of Vertriebene (expellees) out of the former German areas such as Silesia, Pomerania, and East Prussia had ceased. Then, in the early 1950s, some 40,000 "latecomers" from Poland were transferred to West Germany by the Red Cross. The emigration of the first Aussiedler from Poland was subsequently arranged in the late 1950s on the basis of "family reunion."(51) Between 1956 and 1959, 247,766 people chose this path to Germany. However, there were already at that time many exit applications primarily for economic rather than for family-related reasons.(52) The numbers declined in the 1960s, but the Polish German Treaty of 1970 opened new opportunities for persons claiming German ancestry. A "whole little industry" was born to produce documents on a grandfather in the Imperial Army or other German roots, as Wladyslaw Bartoszewski once remembered with a smile.(53)

The number of Aussiedler migrating from Poland to Germany rose dramatically again after 1980/81. The majority of Polish Aussiedler found Northern Germany including Hamburg more attractive than ethnic Germans from other regions of Eastern Europe who preferred the South: in the years 1971 to 1988, 18,577 of the 579,547 Aussiedler from Poland settled in Hamburg.(54) After figures peaked again in 1989, the legal possibilities for the entry of Aussiedler from Poland were narrowed. For this "ethnically privileged migration"(55) the motives for coming to Germany included fear of or actual experience of repression in Poland, longing for a German-speaking environment, desire for family reunion, and the expectation of better economic living conditions.

Not all Aussiedler from Poland took part in Polish life in Hamburg, but a considerable number of them took advantage of its offerings. Considering the fact that, after 1945, Germans in Poland were subjected to Polonization and lived in a Polish-dominated milieu, one can assume that decades later they brought cultural traditions with them that were closer to Polish than to German culture.(56) They also were often married to Poles and their children were born in Poland; yet entire such families would come to Hamburg. Therefore it is necessary to take into account at least some members of this group with proved "German ethnic origin." (57)

The immigration of such a high number of Aussiedler added another divisive aspect to Polish life in Hamburg. Differences were of a less political nature and had their origin in a very "German" attitude of the Aussiedler who had grown up in Poland. This might have been encouraged by the pressure to behave and show off as Germans in order to be accepted as the echte Deutsche and given all the privileges of this legal status by the German authorities. E.g., in 1971, one of the first German-Polish events was organized in a church in Hamburg.(58) The young Aussiedler from Poland--all of them speaking in Polish--hosted a postcard exhibition in little booths representing each Polish region, while at the same time young members of a Polish dance group--all speaking in German--changed for their show in the next room. There was no communication at all between the two groups: an atmosphere of deep mutual rejection prevailed. The "Poles" warned each other against the "Germans"--in German--and the "Germans" did the same in Polish. Another example: when the children of a kindergarten were invited to attend a performance by a Polish theatre company, the parents of Aussiedler children did not allow them to go.(59) A third case has to do with a former DP's bitterness about marginalization of Polish traditions in a church after an increasing number of Aussiedler had joined the congregation. The church had been a home to Polish services by the end of the 19th century.(60) Teachers of the first Aussiedler classes in the late 1950s observed two diametrically opposed attitudes among their students: some missed Poland and were full of prejudice and resentment towards Germany; others aimed to forget about everything Polish.(61)

In terms of social life and contacts, however, the political division among Poles in Germany was hugely overestimated.

However, this division was personal and social rather than political. On the one hand, there were "real" Poles who had been living in Germany for a very long time, on the other, there were "real" ethnic Germans who had been living in Poland for many years. The separation was primarily due to problems of acceptance, problems with a "Polish" image prevalent in Germany. Only after 1990 could some voices be heard suggesting that Aussiedler were part of Polish life abroad.(62) Earlier research focused exclusively on their integration in German society. Yet there had always been Aussiedler participating in Polish life in Hamburg. Only one member of the family had to be German to allow all of them entry to Germany. So we have got the young boy who was not happy about his parents' migration to Germany and joined Zgoda in the 1960s to practice his native Polish and meet other Poles (eventually including his wife, daughter of former forced laborers).(63) Another example is the man who was looking for Polish-speaking friends for his Polish wife: both became members of Rodlo in the 1960s.(64) Others joined Zgoda or Rodlo mainly because of the possibility of traveling to Poland where they still had family. Still others, mainly among the older generations, decided for a membership in German expellee organizations (Homeland Societies) instead.

Until 1980 the majority of migrants from Poland came as Aussiedler. One exception was a small group of political refugees in 1968 when the anti-Zionist/anti-Semitic campaign in Poland forced Jewish Poles to leave.(65) Because of the political upheaval and economic crisis in Poland after Solidarity was delegalized in December 1981, legal opportunities of immigration as Aussiedler were largely taken advantage of, as it was the best way to be allowed to stay in Germany after the flight from the People's Republic.(66) Many more, however, sought refuge in the West, and thousands sought acceptance as asylum seekers in the Federal Republic. Hence the 1980s brought the largest number ever of people with a Polish passport to Germany. In Hamburg, the number of foreigners with Polish nationality increased from 1,142 in 1977 to 20,979 in 1990.(67) With these migrants the structure of Polish life in Hamburg changed completely. Among them were "intellectuals" and "artists," as some older immigrants mockingly called them. Their political socialization was quite different from that of the older migrants. Some participants in Polish life in Hamburg also remember the new immigrants' sarcastic remarks about the linguistic mistakes the old immigrants were making when speaking Polish.(68) But this influx brought new energy and drive to Polish life. Klub Polski, where Poles have been meeting since 1968, became a center for common activities in support of the people in Poland and also a center of information for the new arrivals.(69) But when the borders were opened after 1990, the interest for Klub Polski and other organizations went down. New forms of Polish life emerged, but this is no longer my topic as conditions and problems of research are now quite different.(70)

Summing up, there is and was a Polish life in Hamburg and elsewhere in Germany, a cultural and political life organized by people from Poland by means of various circles and organizations. There exists a network of quite a few people with Polish background. Nonetheless Polish life never played a prominent role in West German public life, and Poles were seldom noticed in the society of the Federal Republic until 1990.

Most Germans have never developed a comprehensive understanding of Polish life: after 1945, German society was no longer aware of the fact that, since 1918 and earlier, people with a Polish background have lived among them. Their situation was ignored and forgotten by the Germans. The Catholic press was the sole exception; it wrote about issues linking Hamburg and the Poles from 1969 onwards, when West Germany's Ostpolitik changed the state's attitude towards Poland.(71) In the 1970s, when the public debate on Gastarbeiter started, the alleged positive example of the "integrated Ruhr Poles" was remembered but without looking at the current situation of Poles in the country. Right after 1945, no one thought about the "old" Polish emigrants amid the German population. More visible--although only for a moment--were the "new emigrants," or thousands upon thousands of deported Poles liberated by the Western Allies. In the summer of 1945 forced laborers, who had previously been exploited, were seen as a threat. Tales of crimes committed by them and their involvement in the black market after liberation are still alive.(72)

After the occupation of West Germany by the Western Allies had come to an end in 1949, the number of Poles was reduced drastically everywhere in Germany, and their fate again was unnoticed. Later on, when the "Ruhr Poles" were remembered as the role models of well-integrated migrants, no one thought about the Poles who immigrated (or had been deported) later and lived in Germany as stateless persons, or as Polish or German citizens. It was only after Solidarity came to life in 1980/81 that Poland's political fate and its refugees were seen and to some extent supported. Maybe only then was a kind of Polish community functioning for a while, ignoring all disagreement between the groups.

How Polish immigrants have felt about Germany and Germans is a different story. Old fears and old prejudices were always alive on both sides. The majority of Polish immigrants, whether refugees or Aussiedler, experienced anti-Polish prejudice, and many of them tried to hide their past and tradition.

FOOT NOTES- This is exceptional in migration history. See Stefanski 1995; Wolff-Poweska/Schulz 2000; Korcelli 1994.

- A term without any connection to their fate as forced migrants. See Jacobmeyer

1985, p. 231.

- Aussiedler are ethnic Germans coming from outside Germany. This status

could, and in some East European areas still can be claimed by all persons

(as well as their descendants and close relatives) who lived within the borders

of Germany of 1937 or who were German citizens in 1939-45 but lived outside

those borders; and by other ethnic Germans. Between 1950-92 2.9 million Aussiedler

immigrated, half of them from Poland. In 1992 the law was restricted and

Aussiedler from Poland were not accepted any more. See Rudolph 1994, p. 118;

Baaden 1997.

- Cyrus 1999 and Miera 1997. See also some papers in Pallaske, ed., 2001.

- Collected in "Werkstatt der Erinnerung" (WdE) in the Forschungstelle

für Zeitgeschichte in Hamburg.

- The Polish Consulate in Hamburg estimates that there are 100,000 Poles

in Hamburg. See Konsul Krzesinski in: die tageszeitung (Hamburg issue), 11

August 2000, p. 23; Statistisches Landesamt, Hamburg, 31 December 1999, states

that the population of Hamburg was 1,704,755; with foreign passports 261,871;

with Polish passports 19,072. The largest foreign group are Turks followed

by Yugoslavs.

- Blecking 1984, p. 54; Oenning 1991.

- Polonia w Europie 1991, p. 23; Kleßmann 1978, still the basic study

on "Ruhrpolen," and for Berlin Hartmann 1991, Poniatowska 1996.

Poles from the Prussian partition who migrated to the Ruhr were officially

of "Prussian" nationality. Broszat 1981, 3rd ed., Hauschildt 1986,

pp. 12, 286. Wilhelmsburg, Schiffbek, Altona and other places became parts

of Hamburg only in 1937, but are considered for my project from 1918 on.

Hauschildt 1986, p. 34f; Nadolny 1992, p. 15. - Herbert 2001, ch. I.1 and I.2.

- Broszat 1981, 3rd ed., p. 289 f.; Pallaske 2001.

- As in Wolff-Poweska/Schulz 2000, p. 1 f.

- Strauss-Quinn 1994.

- Zwak 1985; Nadolny 1992. StA HH 231--10 Amtsgericht Hamburg--Vereinsregister:

B 1973-24 Polskie Towarzystwo Szkolne na Hamburg i okolice, Hamburg, 1925-1940.

- See announcements and adverts in Nachrichtenblatt für die katholischen

Gemeinden Hamburgs. 1924 (1)- 1936 (13).

- Forycki 1984, p. 194. StA HH 132-1 II B 1 49: List of names of interned

Poles, 30 October 1939.

- The estimates vary between 1,7 million and over 3,5 million. Stefanski

1995, p. 391; üuczak 1991.

- 3,273 men and 2,527 women made up 11.4 percent of all forced laborers

in Hamburg during the Second World War. Friederike Littmann, an unfinished

dissertation on "foreign work" in Hamburg, 1939-1945.

- Davies 1989, p. 72 f. Many Polish soldiers imprisoned in the first years

of war were forced to accept the status of forced laborers. See interviews

FZH WdE 283, 341, 342. Interviews with fighters in the Warsaw Rising: FZH

WdE 458, 461, 661.

- See Jacobmeyer 1985 on DP policy; Wagner 1997 on Polish DPs in Hamburg.

- Stefanski 1995, p. 394.

- Stefan Liman of Instytut Zachodni in Poznan quoted different tables of

German statistics as of 29 October 1946: Liman 1975, p. 57.

- PRO WO 171/8159 War Diary Apr.--December 1945. In November 1945 there

were over 17,000 Polish DPs in Wentorf, see Wagner 1997, p. 20.

- There were over 800,000 Poles in the Western zones. Jacobmeyer 1985,

p. 83.

- Jacobmeyer 1985, pp. 64 ff., 86 f., 116 ff.

- FZH WdE 461.

- See an interview with an active member in Wagner 1997, pp. 145-8.

- Nadolny 1992, pp. 42-46, 62. Associations were not allowed earlier. But

the first steps were undertaken in 1945. Zwak and Poniatowska/Liman/Kreìalek

1987, pp. 145-8.

- FZH WdE 647.

- Schmiechen-Ackermann 1992, pp. 192 ff. FZH WdE 639 and 662.

- FZH WdE 461, 661.

- FZH WdE 461.

- FZH WdE 661.

- FZH WdE 458, 461, 641, 661.

- FZH WdE 641. Between 1956-66 and after 1983 the High Mass in Polish was

held at St. Joseph's in Altona. Nadolny, p. 73.

- Zgoda, e.g., "'Zgoda'--der Arm Warschaus in der Bundesrepublik," Wehr-pol.-Information,

Köln (4 September 1969), 7-8.

- Wagner 1997, p. 20; StA HH 352-8/7 190; Jacobmeyer 1985, pp. 92-6. In

protest, all Polish military missions (the consulates of People's Poland)

were closed in protest in December 1950. PA AA B 11 373.

- Reports by German officials always showed suspicion of Soviet infiltration

via communists in Polish organizations. See PA AA B 11 571, internal report

dated November 1951 and titled "Poles in the Federal Republic of Germany."

- Quote by Maksymilian Pelc in Wagner 1997, p. 145.

- FZH WdE 461, 638; Forycki 1984, p. 194; Ruchniewicz 2001, p. 66 f.

- See for example Zwak 1985, Kucharski 1976.

- Wir Hamburger aus Polen 1993, 2d ed.

- Davies 1989, p. 25.

- This was the case with the father of Kasia Dombrowski (a pseudonym).

FZH WdE 641.

- Those "old emigrants" were for example Tadeusz åmietana

from Zgoda, already active in the Polish school association, and Aleksander

Mlody from Rodlo. Kucharski 1976, pp. 22 and 24; Zwak 1985, p. 160; FZH WdE

638, 647.

- Ruchniewicz 2001, p. 66 f.

- Later on, the main attraction of both Zgoda and Rodlo seems to have been

an offer of reduced visa and group travels to the People's Republic.

- StA HH 363-3 II 30-035.27/21 Band I: Haus der Begegnung (1958-67).

- Wagner 1997.

- Nadolny 1992.

- Familienzusammenfürung was the motto of the first project. For the

entire Aussiedler question see the essay by Wisniewski including German and

Polish figures.

- Wisniewski 1992, p. 165, quotes J. Korbel, Wyjazdy i powroty. Migracje

ludnosci w procesie normalizacji stosunków miedzy Polska a RFN (Opole,

1977), pp. 131-44; Polska ludnosc rodzima. Migracje w przeszlosci i w perspektywie

(Opole, 1986), pp. 135-40.

- An interview in Hamburg, 16/17 June 2000.

- Schwinges/Kiehl 1989, pp. 15, 42; Wisniewski 1992, p. 166.

- The subtitle of Münz/Ohliger 1996.

- Urban 1993, pp. 67-86; Münz/Ohliger 1998, p. 165 f.

- In short reference essays, Aussiedler are always included as part of

the "Poles in Germany" formation. See Meister 1992, 3.1.1.-28 to

32; Stefanski 1995, p. 397; Wolff-Poweska/Schulz 2000, Pallaske 2001, Cyrus

1999.

- Hanno Jochimsen. Wir riefen auf zum Frieden 1997, p. 10.

- FZH WdE 641.

- E.g., the celebration brochure, FZH WdE 461.

- StA HH 361-2 VI 695 (Schulleiter Bülaustrasse an Schulbehörde,

February 1956).

- In the study on Aussiedler integration in Hamburg this question was still

ignored. Schwinges/Kiehl 1989.

- FZH WdE 640.

- FZH WdE 638.

- Kosmala 2000; Keim 1997.

- Pallaske 2001; Schmidt 2000.

- Statistical reports: Foreigners in Hamburg, A I 4: j/77 (20 September

1997), states that out of 125,861 aliens 1,142 were Poles; j/84 (20 September

1984): 164,718 aliens, 7,830 Poles; j/90 (31 December 1990): 20,979 Poles.

- FZH WdE 640.

- A report by Pelc in Wagner, p. 146 ff.

- Miera 1997, Cyrus 1999, Pallaske 2001, Warchol-Schlottmann 2001.

- Kirchenbote des Bistums Osnabrück, Kirche am Strom, e.g., No. 13

of 30 March 1969.

- Herbert 1999, p. 397 ff.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

FZH WdE + number indicates an interview from the oral history collection

Forschungsstelle für Zeitgeschichte in Hamburg,Werkstatt der Erinnerung

PA AA: Political Archives of the Foreign Office (formerly in Bonn, now in

Berlin)

PRO: Public Record Office, Kew, Britain

StA HH: Staatsarchiv Hamburg

- Andreas Baaden, Aussiedler-Migration: Historische und aktuelle Entwicklungen (Berlin, 1997).

- Diethelm Blecking, "Über die Ruhrpolen und den deutschen Polendiskurs," Kulturrevolution, No. 7/1984, pp. 54-56.

- Martin Broszat, Zweihundert Jahre deutsche Polenpolitik, 3rd ed. (Frankfurt am Main, 1981).

- Norbert Cyrus, " Einwanderung und Mobilität. Die Relevanz mobiler Lebensformen für die Integration von Zuwander/innen aus Polen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland" (a conference paper, to be published in a volume dedicated to the Workshop on "Immigranten aus Mittel-Ost-Europa: Italien und Deutschland vor der Herausforderung ihrer Aufnahme in Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft," 5- 6 November 1999, Forli, Italy).

- Norman Davies, "The growth of the Polish community in Britain 1939-1950," Keith Sword with Norman Davies and Jan Ciechanowski, The formation of the Polish Community in Great Britain, 1939-1950 (London, 1989), pp. 17-84.

- P. Edmund Forycki, "Die polnische Minderheit in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland," Europa Ethnica 47/1984, No. 4, pp. 193-98.

- Gottfried Hartmann, "Polen in Berlin," Von Zuwanderern zu Einheimischen. Hugenotten, Juden, Böhmen, Polen in Berlin, edited by Steffi Jersch-Wenzel (Berlin, 1991), pp. 593-800.

- Elke Hauschildt, Polnische Arbeitsmigranten in Wilhelmsburg bei Hamburg während des Kaiserreichs und der Weimarer Republik (Hamburg, 1986).

- Ulrich Herbert, Fremdarbeiter. Politik und Praxis des "Ausländer-Einsatzes" in der Kriegswirtschaft des Dritten Reiches, new ed. (Bonn, 1999). ___________, Geschichte der Ausländerpolitik in Deutschland. Saisonarbeiter, Zwangsarbeiter, Gastarbeiter, Flüchtlinge (München, 2001).

- Wolfgang Jacobmeyer, Vom Zwangsarbeiter zum Heimatlosen Ausländer. Die Displaced Persons in Westdeutschland 1945-1951 (Göttingen, 1985).

- Inken Keim, "Eine Biographie im deutsch-polnischen Kontext: Marginalität, kulturelle Uneindeutigkeit und Verfahren der Tabuisierung," Polen und Deutsche im Gespräch, edited by Reinhold Schmitt and Gerhard Stickel (Tübingen, 1997), pp. 253-303.

- Christoph Kleßmann, Polnische Bergarbeiter im Ruhrgebiet 1870-1945. Soziale Integration und nationale Subkultur einer Minderheit in der deutschen Industriegesellschaft (Göttingen, 1978).

- Piotr Korcelli, "Emigration from Poland after 1945," European Migration in the Late Twentieth Century. Historical Patterns, Actual Trends, and Social Implications, edited by Heinz Fassmann and Rainer Münz (Aldershot, 1994), pp. 171-185.

- Beate Kosmala, editor. Die Vertreibung der Juden aus Polen. Antisemitismus und politisches Kalkül (Berlin, 2000).

- Wladyslaw Kucharski, Zwiazek Polaków Zgoda w Republice Federalnej Niemiec (Lublin, 1976).

- Stefan Liman, "Polacy w Hamburgu w latach 1946-1975," Przeglad Zachodni, 4/1985, pp. 47-61.

- Czeslaw üuczak, "Polnische Arbeiter im nationalsozialistischen Deutschland," Europa und der "Reichseinsatz." Ausländische Zivilarbeiter, Kriegsgefangene und KZ-Häftlinge in Deutschland 1938-1945, edited by Ulrich Herbert (Essen, 1991), pp. 90-105.

- Hans-Peter Meister, "Polen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland," Handbuch ethnischer Minderheiten in Deutschland, edited by Berliner Institut für vergleichende Sozialforschung (Berlin, 1992), par. 3.1.1.-1 to 3.1.1.-57.

- Frauke Miera, "Migration aus Polen. Zwischen nationaler Migrationspolitik und transnationalen sozialen Lebensräumen,"

- Zuwanderung und Stadtentwicklung, edited by Hartmut Häußermann and Ingrid Oswald (Wiesbaden, 1997), pp. 232-254.

- Rainer Münz and Rainer Ohliger, Deutsche Minderheiten in Ostmittel- und Osteuropa, Aussiedler in Deutschland. Eine Analyse ethnisch-privilegierter Migration. DFG-report (Berlin, 1996).

- Rev. Anastazy Nadolny, Sto lat polskiego duszpasterstwa w Hamburgu, 1891-1991 (Hamburg: Polska Misja Katolicka, 1992). v Ralf Karl Oenning, "Du da mitti polnischen Farben...," Sozialisationserfahrungen von Polen im Ruhrgebiet 1918 bis 1939 (Münster-New York, 1991).

- Christoph Pallaske, editor, Die Migration von Polen nach Deutschland. Zu Geschichte und Gegenwart eines europäischen Migrationssystems (Baden-Baden, 2001).

- ____________, "Die Migration von Polen nach Deutschland seit 1980," Die Migration von Polen. . ., pp. 123-140. Polonia w Europie (Poznan , 1992).

- Anna Poniatowska, Stefan Liman, and Iwona Kreìalek, Zwiazek Polaków w Niemczech w latach 1922-1982 (Warsaw, 1987).

- Anna Poniatowska,"Die Polen in Berlin," Zwischen Abgrenzung und Assimilation--Deutsche, Polen und Juden. Schauplätze ihres Zusammenlebens von der Zeit der Aufklärung bis zum Beginn des Zweiten Weltkriegs, edited by Robert Maier and Georg Stöber (Hannover, 1996), pp. 65-77.

- Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, " Die polnische politische Emigration nach Deutschland in den Jahren 1945 bis 1980," Pallaske, editor, pp. 61-75.

- Hedwig Rudolph, "Dynamics of Immigration in a Nonimmigrant Country, Germany," European Migration in the Late Twentieth Century: Historical Patterns, Actual Trends, and Social Implications, edited by Heinz Fassmann and Rainer Münz (Aldershot, 1994), pp. 113-126.

- Jacek Schmidt, "'Aussiedler'-zwischen Polen und Deutschen," Anna Wolff-Poweska and Eberhard Schulz, editors, pp. 270-287. Detlef Schmiechen-Ackermann,"Zwischen Integration und Rückzug in das Sozialmilieu einer nationalen Minderheit: Polnische Zuwanderer in Misburg 1880-1930," Am Rande der Stadt, edited by Hans-Dieter Schmid (Bielefeld, 1992), pp. 143-220.

- Ulrich Schwinges and Klaus Kiehl, Die Eingliederung von Aussiedlern. Eine empirische Untersuchung in Hamburg (Hamburg, 1989).

- Valentina Maria Stefanski,"Die polnische Minderheit," Ethnische Minderheiten in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Ein Lexikon, edited by Cornelia Schmalz-Jacobsen and Georg Hansen (München, 1995), pp. 385-401.

- Claudia Strauss and Naomi Quinn, "A Cognitive/Cultural Anthropology," Assessing Cultural Anthropology, edited by R. Borofsky (New York, 1994), pp. 284-298.

- Thomas Urban, Deutsche in Polen. Geschichte und Gegenwart einer Minderheit (München, 1993).

- Patrick Wagner, Displaced Persons in Hamburg. Stationen einer halbherzigen Integration 1945-1958, edited by Galerie Morgenland (Hamburg, 1997).

- Malgorzata Warchol-Schlottmann, " Polonia in Germany," Sarmatian Review, vol. XXI, no. 2 (April 2001).

- "Wir Hamburger aus Polen," by Elìbieta Górska and Alexandra Kuzminska-Wojtyllo, 2d ed. (Hamburg: Ausländerbeauftragter der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg, 1993).

- Wir riefen auf zum Frieden. 25 Jahre Deutsch-Polnische Gesellschaft 1972-1997 (Hamburg, 1997). Zenon Wisniewski, "Aus Polen--nach Deutschland. Zahlenmäßige Entwicklung und Integrationsprobleme der Aussiedler," Osteuropa, no. 42(1992), pp. 160-170.

- Anna Wolff-Poweska and Eberhard Schulz, editors, Polen in Deutschland. Integration oder Separation? (Düsseldorf, 2000).

- Irena Zwak,"Zwiazek Polaków w Niemczech-Oddzial Hamburg (1922-1982)," Studia Polonijne (Lublin), No. 9 (1985), pp. 157-163.